The 1951 Season

Expanding Into New Frontiers

By Greg Fielden

|

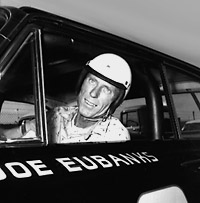

| Joe Eubanks finished 10th in the 1951 point standings. |

One of the major factors in the immediate success of NASCAR's Grand National division was the fact that the Southeast finally had a sport which it could call its own. For decades the Southeast had been starving for a place in the arena of big time sports. There was no major league baseball team to support. Nor was there a professional football franchise. No Southern city had a pro basketball team.

Even the sport of auto racing rarely made stops below the Mason-Dixon line. The American Automobile Association (AAA), which sanctioned Indianapolis-type open wheel racing from 1902-1955, scheduled few championship meets in the South except for an occasional show at Atlanta's Lakewood Speedway. When Bill France orchestrated the Grand National circuit, the Southern sports enthusiast who had labored long and hard with a lack of identity, welcomed stock car racing with open arms.

In 1949 and 1950, the Grand National tour made 27 stops at 14 different tracks in eight states. The farthest West NASCAR ventured was a 100-miler in Winchester, Indiana. France felt he needed to expose his rambunctious stock jockeys to the West coast--and he was able to secure six events in the far West in 1951. In addition to NASCAR's stretching well beyond its home base in Daytona Beach, France felt he needed a nationally known figure to be in the Grand National fold. He found a savior of sorts in Bill Holland, winner of the 1949 Indianapolis 500.

Holland was one of the AAA's flashiest speed artists. In 1947, as a rookie at the "Brickyard," Holland was asked by car owner Lou Moore to drive the second car in his team which was headed by the idolized Mauri Rose. Moore needed the second vehicle in case Rose's car failed to make the distance. If that happened, Rose could perhaps take over the driving chores in the second car. Bill Holland did not know the rules. He had the 500 virtually tucked away when Moore ordered him to back off via the pit board which read "E-ZY." Holland followed Moore's instructions and slackened his pace in the waning laps as running-mate Rose closed the gap dramatically.

Holland, thinking Moore's message meant he had a full lap on the field, waved as Rose motored into first place with nine laps to go. When the checkered flag fell, Holland cruised over to victory lane only to find Rose was already there, sharing the accolades with car owner Moore. Holland was livid. He could not believe that Moore had beguiled him in the world's most important auto race. And he exercised little restraint in his post race comments. The racing fraternity rallied behind the Miami newcomer.

"NASCAR has outgrown its expansive plans and has set the pace the entire country followed."...Illustrated Speedway News, 1951.

In 1948, Rose again won the Indianapolis 500 with Holland second as the Moore team registered another one-two finish; this time the outcome was untarnished by questionable tactics. The following year, 1949, Holland finally captured the greatest spectacle in racing by winning the Indianapolis 500. He finished second the following year in a rain-shortened 500. Bill Holland's name was widely recognized from coast to coast.

During the winter of 1950-1951, Holland was requested by promoters of a short track in Opa Locka, Florida, to drive in a three-lap Lion's Club event to raise funds for various Club charity projects. Holland graciously accepted without charging an appearance fee.

He drove in the three-lap event on the small dirt oval, and the fund raising campaign was considered a success. When the AAA Contest Board got wind of Holland's deed, they promptly suspended him for the entire 1951 season. In fact, it was not until 1954 that Holland was reinstated by the AAA in what was the most outrageous reprimand ever levied against an American auto racer.

Enter Big Bill France. He befriended the fallen AAA star and said he would help arrange a ride if Holland would join NASCAR. Not having anywhere else to race, Holland accepted France's offer. France put Holland in the driver's seat of the 1950 Plymouth that had won the inaugural Southern 500--an automobile originally owned by France and Alvin Hawkins, and prepared by Hubert Westmoreland. Holland drove in seven Grand National races, enjoyed one top five finish and earned a total of $535. The car was crashed heavily in a turn-over at Charlotte. Despite the lack of success, France and NASCAR got plenty of mileage from Holland's mere presence in the starting field.

|

| Marvin Panch made three Grand National starts in 1951. |

By early summer of 1951, the Junior Chamber of Commerce of Detroit was preparing to celebrate the 250th anniversary for the Motor City. Located within the city limits was the old Michigan State Fairgrounds and located within the fairgrounds there just happened to be a one-mile dirt race track. What better event for the Motor City celebration than a race between automobiles primarily built in the Detroit area?

Again Big Bill France came to the rescue. He convinced the leaders of the celebration that a stock car race featuring Detroit autos would be an ideal supplement for the gala festival. They agreed. A 250-lap contest, one lap for each of the 250 years, was slated for August 12th. France campaigned diligently for each of the automobile manufacturers, who previously had only a passing interest in stock car racing, to place at least one make of their car in the race.

At post time, a field of 59 cars had qualified, and no less than 15 different makes of cars, were on the starting grid. A crowd of 16,352 jammed the Fairgrounds to watch the event. High level representatives from virtually every manufacturer were on hand. The event was an unabashed slugfest with Tommy Thompson, manning a huge Chrysler, out-dueling Curtis Turner in an epic finish. Stock car racing, NASCAR style, was a big hit in the Motor City. An editorial which appeared in Illustrated Speedway News, read: "The stock car picture (has never) been brighter. NASCAR has outgrown its expansive plans and has set the pace the entire country followed. The gigantic Detroit 250-mile race served as the impetus that cracked the Maginot line of defense thrown up by the motor industry against the sport. They know we're here."

NASCAR threw the green flag on another racing division in 1951 -- the Short Track circuit. With the demand for NASCAR late model events, France opted to start another circuit for Grand National-type cars on tracks shorter than a half-mile in length. Eleven Short Track events were staged in 1951 and Roscoe "Pappy" Hough was crowned champion. Sanctioning NASCAR suspended and/or fined a number of drivers during the 1951 Grand National campaign, most notably, Marshall Teague. Teague, the original NASCAR treasurer, had opened the door for auto manufacturers to support individual racing teams when he sold stock car racing and himself to the Hudson Motor Co. Hudson then backed the fabulous Hudson team owned by Teague. This set the stage for future financial and technical support.

Teague, whose ambitions had always included Indianapolis, lost all points he had earned at mid-season for competing in a AAA stock car race. Other drivers who were suspended, fined and stripped of points were Curtis Turner, Jack Smith, Bob Flock, Billy Carden, Ed Samples, Jerry Wimbish, and, for the second time in as many years, 1949 champ Red Byron. For the season, Herb Thomas won seven races, including the second annual Southern 500. He was the Grand National champion by 146.2 points over eight-race winner Fonty Flock.

NASCAR gained many strides in 1951 and even had to battle near-sighted politicians who were lobbying the Congress to ban all auto racing. In North Carolina, California and New Jersey, bills were proposed to "prohibit and curtail all forms of auto racing." Enter Big Bill France. He addressed the threat and was a factor in the Congressional bill never getting to the floor.